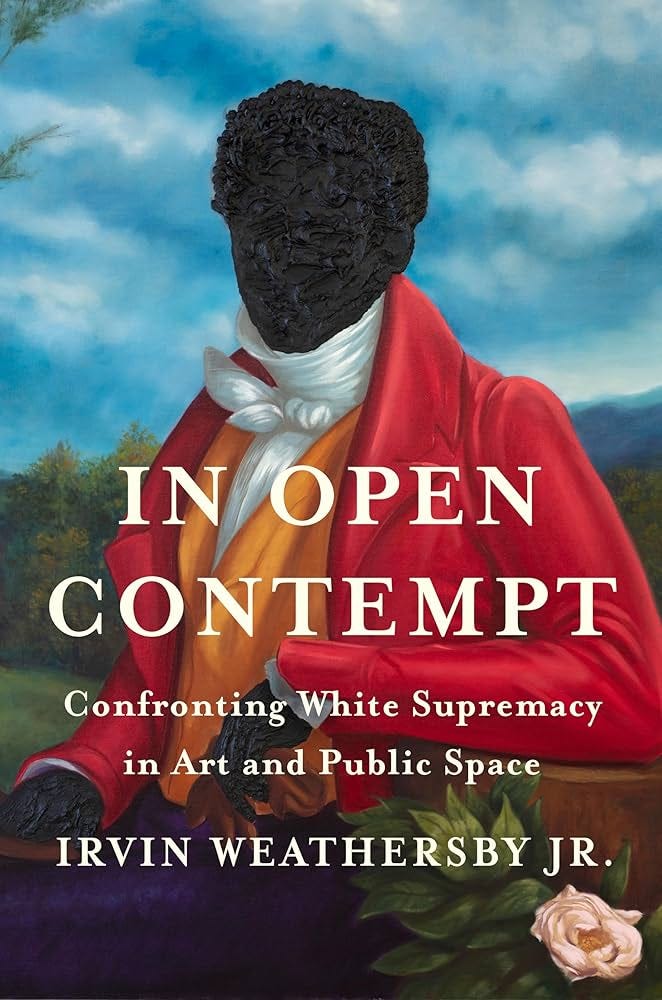

I just finished listening to Irvin Weathersby’s “In Open Contempt: Confronting White Supremacy in Art and Public Space.” When I listen to a book about wandering — in the book, Irvin wanders the world expounding on the racist history behind the art we consume and celebrate — I like to wander as well. Walking the streets of Philly, I experienced a small thrill each time Irvin began to describe a work of art by a Black artist that I’d seen before.

A few years ago, I decided I would be the type of person who traveled for art. Living in Louisville, KY at the time, we rarely got the big exhibits by the contemporary Black artists I admire. First I traveled to Chicago to see the Bisa Butler exhibit there, where Black matriarchs crowded the museum dressed in their Easter’s finest to return the glory Bisa bestows on our people with her vibrant quilts.

Most recently, I took the Amtrak up to NY — something that’s quickly become a regular occurrence for me. I’ll certainly be trekking back to the Big Apple to see the Amy Sherald exhibit — for my bestie’s b-day, and then dragged our crew to the Whitney to see the Alvin Ailey exhibit, which nearly brought me to tears as I stood with my back to an AIDS quilt and read the text about the last years of Ailey’s life as I could hear the audio from the video playing in the main gallery of Ailey’s dancers wishing him well and hoping he’d return to the studio soon, knowing as my eyes progressed through each sentence, that their wishes would go unfulfilled.

On my birthday trip to Atlanta to see the GIANTS exhibit there, I note to my bestie each artist whose work I recognized even without reading the wall text. I also realized that I’d been exposed to quite a few of these artists for the first time in Louisville — thankful to the curation at 21c and Miranda Lash’s time as curator at the Speed Art Museum. Lash is now in Denver at the Contemporary Art Museum, where I first encountered the work of Rashid Johnson. I briefly considered moving into a Philly apartment complex because they had a piece of his on display in the lobby. It was also in Denver that I saw the sound suits of Nick Cave for the first time.

Recognizing artists by their work feels an accomplishment for me as someone who didn’t understand in school how it was possible. Turns out, I just hadn’t been exposed to enough art, regularly enough to do so and I had not spent vast amounts of time in the presence of art that connected with my spirit. Achieving both of those, the skill came easy to me.

I did not know that Irvin’s travels took him to Louisville. I was deeply moved by his experience of the art exhibit at the Speed museum in honor of Breonna. I’d seen the same exhibit, taken in the same local photography of the protests, was haunted by the same Sweet Honey in the Rock singing, and stood before the same wall-sized Amy Sherald painting of Breonna Taylor.

Irvin writes about a painting by Kerry James Marshall. I am now familiar with Marshall’s work, but I must not have been at the time of the Breonna Taylor exhibit or I was so emotionally overwhelmed by the exhibit that I did not take note of Marshall’s “BB” from his Lost Boys series. Irvin explains that Marshall uses Peter Pan’s Lost Boys as a metaphor for Black boys who’ll never grow up, not because they don’t want to, but because their lives were cut short before they could do so.

In the story of Peter Pan, Wendy, the girl who mothered the Lost Boys, leaves Neverland, marries and has actual children of her own. I wonder then about the mothers these Black Lost Boys leave behind, like a parade of Wendys moving in reverse to a time when their boys were still here. I think about the image of the strong Black mother, determined even in her grief, the one set by Mamie Till-Mobley. How these mothers have little choice but to serve as engines and icons for the movement.

The same week I listen to Irvin tell me about Marshall’s painting, I’d written about Peter Pan and Wendy as part of a project I’m working on. Yes, maybe these boys refuse to become men, to remain in Neverland forever, but doesn’t Wendy decide to grow up in the end? I had to check Wikipedia because honestly I wasn’t sure. It’d been decades since I’d seen the Disney movie, I don’t think I ever read the book and “Hook!” wasn’t a life defining movie for me, the way it seemed to be for the teen boys I surrounded myself with during my younger years.

Why is it that boys and men romanticize male-only spaces? When we see so often how these spaces are breeding grounds for oppression and abuse — the military, sports, boardrooms. Then they resent women and nonbinary folks when we infiltrate what they viewed as solely their domains. Would they be more willing to welcome us into these spaces if their boyhood fantasies weren’t contingent on our absence?

Whereas all of women’s prescribed fantasies are about being grown up — playing Barbies, playing house, even the explosion of the Sims in the early aughts.

Anyways, in the original Peter Pan book, Wendy leaves Neverland. When she returns home it’s kind of hinted at that her mother was once a friend of Peter Pan’s too and then once Wendy is grown, Peter Pan comes to collect her own daughter for an adventure in Neverland. Generations of girls and women humoring boys who refuse to become men — why does that sound so familiar?

In the project, I was riffing on dating. One day, whether I liked it or not, I’d grown up, my passport to Neverland forever revoked. And once grown, it was no longer feasible to be in relationship with those who were not. Why is it that women so readily acquiesce to aging, while men, for whom access to power is attained so much easier, so often refuse? Is Peter Pan syndrome actually a rebellion against the Patriarchy? If only so much of the work of adulting they insist they are incapable of did not them fall to the women in their lives, maybe this is a movement I could get behind.

When I tell my cousin I’m mentally riffing on Peter Pan, they tell me on Threads Drake is being accused of refusing to grow up. They send me a clip from Joe Budden’s podcast (content I actively avoid) and he’s in convo with Marc Lamont Hill discussing the new Drake and PartyNextDoor album, which they’ve deemed as all throwaway cuts and PartyNextDoor has defended as songs to fuck to. Marc and Joe are both like — Who is doing what to this?! I’ve not listened to the album, but it’s not hard to accept Drake as someone who has not evolved beyond the age he was when he became famous. The men are calling for him to make music with more mature subject matter, tired of montone-sing-songy raps about scheming on girls in the club. Yawn.

Maybe Andre 3000 was right to pick up that flute.

I regret to inform you that these thoughts have lead me — us? — no where in particular.

I apologize that this installment of the newsletter is so late it slipped into the following week, but my life has been busy and my brain an even busier place, but I’ve had these Peter Pan thoughts percolating for you all week.

I’m teaching another round of Gateway to Memoir for the International Women’s Writers Guild, you do not have needed to be part of the first one to join us in the second round. It kicks off in April.

I’ll be at AWP in LA and reading that Saturday, more details to come. And I’m also the keynote speaker for

Live in NYC Saturday, May 3rd in convo with the homie (whose newsletter I love btw!).